The Darkest Desire

An essay on child photography is violated by secret abuse and personal trauma.

PART I: Minor Indiscretions

‘He thought he knew the girl. Crouching over the light box, it was hard to tell. What was her body like? What kind of nipples did she have? What sort of breasts and thighs? How strangely light and bold the tuft of pubic hair. He has a predatory curiosity which directs his look but what he is offered remains pictures of a girl he thinks he knows.’

—John Tagg, The Burden of Representation.

Our children are captives, held hostage to our fabrications about their collective nature, their individual identities. We dictate who they are, who they must become, denying them their sovereignty, their agency. They so often exist solely to serve our fantasies of immortality, our hunger to reclaim our youth. And other, darker desires. They are, in many ways, the games we play as adults, their autonomy circumscribed by a will that is not their own, their boundless innocence soon sullied by our failure to protect them from ourselves. Perhaps this is why the photography of children is so deeply problematic. We refuse to represent them truthfully, too afraid to see reflected in their naïveté and knowing the worst of what we are.

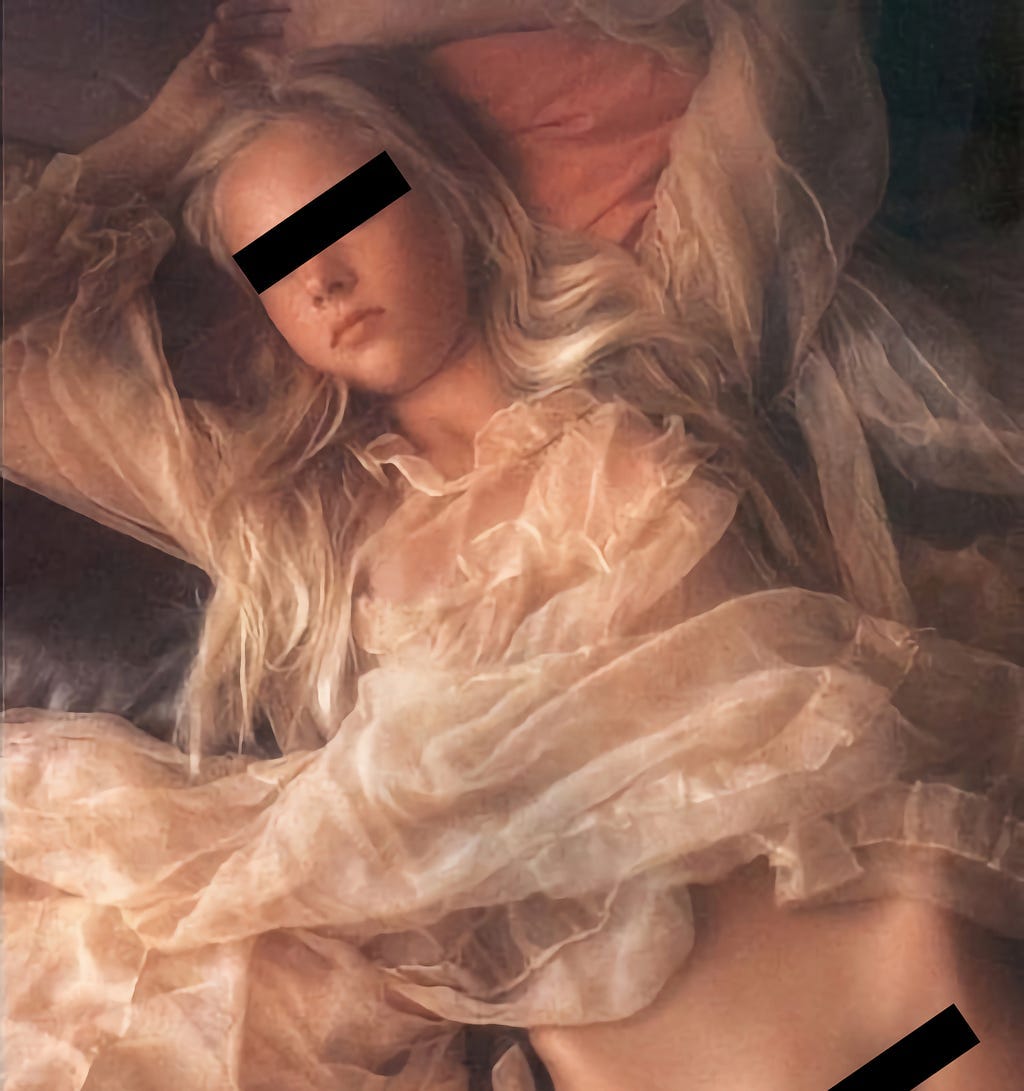

‘Virginity is paradoxically erotic,’ writes Liliane James in her forward to The Age of Innocence, David Hamilton’s menagerie of mannered nude ingenues who, upon reaching this titular stage, become ‘not only physically attractive and beautiful human beings’ but the manifestation of ‘excitements taking shape, and the essence of sexual allure.’ On the pages that follow, his girls are laid bare. They gaze at the viewer with languid, limpid, placid eyes, their naked forms imbued by the lens with what Simone de Beauvoir describes as ‘the freshness of secret springs, the morning sheen of an unopened flower, the orient lustre of a pearl on which the sun has never shone.’ They are compliant, complicit creatures, bright-bodied butterflies delicately unfurled for the eyes to caress, the loins to covet.

And they are all, without exception, minors.

The most disturbing image from this horrifying monograph lies, not in its pages, but on its dust jacket. Shot in mythologising monochrome, it depicts Hamilton with one of his many muses: an angelic, bucolic, gap-toothed girl in a white striped dress. She looks genuinely happy.

The photographer grins beside her. His face is her antithesis — leathery, oily, the caucasian skin preternaturally dark. He wears a plaid sportscoat, a polo shirt with both buttons undone, and thick bifocal spectacles. His enormous right hand cups the girl’s right elbow, long fingers nestled in the crook of her arm, pulling her close. His left hand is an upturned claw, balancing his camera, completing the pincer. There is no background but blackness, an infinite void in which the duo seems suspended, smiling.

I recognise the too-long fingers. I see myself, a child possessed. My mind recoils in fear.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sonder Street to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.